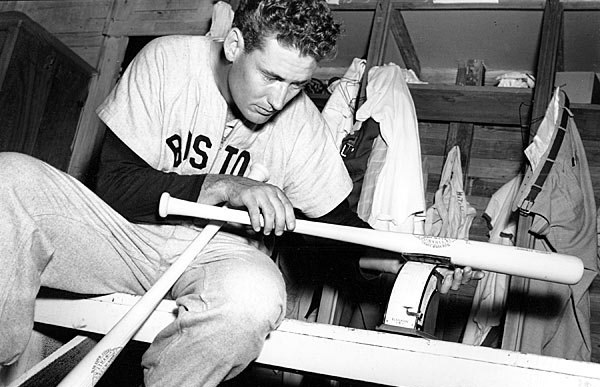

TED WILLIAMS

“THE SPLENDID SPLINTER”

The year was 1939. Ted Williams was travelling to his first training camp, accompanied by manager Bobby Doerr and sportswriter Al Horowitz. Ted began talking about his hitting acumen what must have been seen as insufferable and conceited boasting. Mr. Horowitz countered by stating that the Red Hose had some pretty fair hitters. Al stated: “Wait till you see Jimmy Foxx.” Williams, gazing out the window, and leaned back. “Hmmm”, he said. “Wait until Foxx sees me hit.” *

Major League baseball first took notice of Williams when he began producing prodigious homeruns in the Pacific Coast League. He was soon signed by the Boston Red Sox, for whom he played his entire career, and almost instantly became a star, hitting .327 and hitting 145 RBI’s his rookie year. The marriage of Williams with the Red Sox became dysfunctional like his childhood rather quickly, especially with the Boston Press and the fans. Williams was initially viewed as eccentric but talented. Soon that was changed to self-centered and talented. It is sometimes forgotten that Ted Williams was as hated in his active career, at least by the media, to the same degree as Ty Cobb, Albert Belle, or Rogers Hornsby. (However, he was typically liked, admired, and respected by his teammates) He was born into a dysfunctional family, the son of an indifferent alcoholic and a tambourine shaking mother who was a member of the Salvation Army, as well as a feckless brother. He carried these dysfunctions into his baseball career, as well as into his family life. He refused to pay due deference to the print media, and thus began what was to be 20 years of at times bitter warfare between Ted and the Press, whom he dubbed “The Knights of the Keyboard.” As for the fans, Williams refused to acknowledge them, never doffing his hat after any of his home runs.

A myth that developed was that his eyes were the best in history, being able to see the tread on the baseball as it sped towards the plate at over 90 MPH, as well as read the words on a record album while it was spinning.

Williams’ incredible performance in 1941 is often regarded as one of the greatest hitting seasons in the history of the game. There is the often-told story as to how Williams convinced manager Joe Cronin to allow him to play the final doubleheader of the season, despite the knowledge that he could be jeopardizing his chances to hit .400; we recall that he went 6-8 that day, winding up with a BA of .406. What we perhaps don’t realize is that Williams also led the American League that season in Home Runs and Runs Scored, Bases on Balls, Slugging %, OBP, OPS, and OPS +, and would lead the league in each of the latter five categories for every season he played for the remainder of the decade. (Ted also managed the formidable feat of being as one of the top seven candidates for MVP on 11 occasions.) Of course, Williams’ great season coincided and at the time was over-shadowed by DiMaggio’s 56 game hitting streak; little did the baseball world know that not only wouldn’t the Yankee Clipper’s consecutive game streak be broken, but that no batter would ever hit .400 again. An obscure fact but riveting fact: Williams reached base in 84 consecutive games that season. That ML record has never been broken. In its own way, it is just as impressive as Joltin’ Joe’s streak.

“They can talk about Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb and Rogers Hornsby and Lou Gehrig and Joe DiMaggio and Stan Musial and all the rest, but I’m sure not one of them could hold cards and spades to (Ted) Williams in his sheer knowledge of hitting. He studied hitting the way a broker studies the stock market, and could spot at a glance mistakes that others couldn’t see in a week.” – Carl Yastrzemski

In 1942 Williams had his first Triple Crown year (yet somehow, lost the MVP vote to Joe Gordon of the Yankees). After the season ended, he signed up with the US Marine Corp. He became a fighter pilot, eschewing the opportunity to do a safer gig playing baseball in the Service, which was the course that the majority of major league ballplayers went. Later on, he did a second tour in the Korean conflict. Ted’s amazing hand-eye coordination – perhaps the best in major league history – was demonstrated in Flight School. According to a teammate and fellow serviceman, Johnny Pesky:

“Ted went to Jacksonville for a course in air gunnery, the combat pilot’s payoff test, and broke all the records in reflexes, coordination, and visual-reaction time.” From what I heard, Ted could make a plane and its six ‘pianos’ (machine guns) play like a symphony orchestra,” Pesky says. “From what they said, his reflexes, coordination, and visual reaction made him a built-in part of the machine.”

One of the most memorable performances in All Star History occurred in the 1946 classic, at Fenway Park. Ted Williams had already gone 3-3, with one home run and two singles. Up came the Splendid Splinter in the 8th inning, facing Rip Sewell, he of the eephus pitch. The American League had never seen the like of the eephus. The ball arced upwards up to 20’ in the air, dropping in the strike zone and then into the catcher’s glove as soft as a feather hitting a pillow. No one had ever hit a home run off Sewell’s trademark pitch.

First pitch to Ted: an eephus; foul ball, strike one. Second pitch, fastball; strike two. Third pitch, eephus, ball one. Fourth pitch; as John Sterling, the voice of the Yankees would call it: “It is high, it is far, it is gone!”

As a young boy, Williams had stated that his goal in life was to be the greatest hitter in the game. His career totals don’t to anything to persuade one otherwise. He again won the Triple Crown in 1947. He finished his career with a .344 BA – 7th All Time; had the highest OBP in ML history – .482, had the 2nd highest Slugging % – .534, had the 2nd highest OBP+, was 4th all time in Bases on Balls, 6th in Runs Created, 3rd in Adjusted BA, 2nd in Adjusted Win %; led the league in Home Runs on four occasions, had 521 lifetime dingers; 17th on the all time list, and won the Triple Crown of the Decade for the 1940’s. He was an outstanding hitter well into the latter years of his career, hitting an amazing .388 at the age of 39. In 1957, Williams reached base in 16 consecutive plate appearances, also a major league record. Of course, his lifetime totals were considerably affected by the loss of almost five of his prime playing years while serving his country, as well as playing in Fenway Park, which favored right handed hitters, but which remains a difficult venue for left-handed sluggers. Truth be told, Williams was an indifferent outfielder, although he had a good arm. He was often seen practicing shadow hitting between batters while in the field. Later on in life, he admitted that he could have spent more time focusing on his defense. However, Williams was one of the most technically efficient and gifted individuals of the 20th century; he mastered three different vocations – Ted was the perhaps the greatest hitter of all time; in battle, one of the top ten fighter pilots of his generation. Being a perfectionist in everything he attempted, Williams was famous for his favorite hobby, which was fishing, and could be considered as one of the most proficient recreational deep-sea fishermen of all time. He mastered everything he attempted, including managing – he took the moribund Washington Senators and achieved the impossible – a winning record. Williams was a perfectionist in everything he attempted. He was famous for his favorite hobby, which was fishing, and was as proficient in this arena as in anything else that he seriously attempted to master. He also managed the Washington Senators, and actually achieved the impossible – a winning record with the moribund franchise.

“If he’d just tip his cap once, he could be elected Mayor of Boston in five minutes.” – Eddie Collins (About Ted Williams’ last game, last at bat and his last home run.) In retrospect, Ted admitted that he could have tipped his cap, but stated that would have been out of character for him to do so. That final at bat was immortalized by the author John Updike, in his New Yorker essay, “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu.”

TED’S FROZEN HEAD USED FOR BATTING PRACTICE AT CRYOGENIC LAB!!!

In one of the most bizarre and sad epitaphs of any Major League legend, the world learned of the “Alcor” scheme, where Williams son, John-Henry Williams, managed to convince the authorities that a scribbled signature by his father in his death throes on a scrap of soiled paper allowed him to place his father’s frozen head into storage, in order that it be brought back to life 100 years from now, apparently with the intention of producing thousands of proto-Splinters, in a sordid emulation of the scientific machinations found in the movie “The Boys from Brazil” or the storage of the head of Adolf Hitler by neo-Nazis in the thriller book, “The Day After Tomorrow.” In a Karmic rejoinder, John-Henry passed away in 2004 after a bout with leukemia.

Williams was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame on July 25, 1966. In his induction speech, Williams included a statement calling for the recognition of the great Negro Leagues players:

“…I’ve been a very lucky guy to have worn a baseball uniform, and I hope someday the names of Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson in some way can be added as a symbol of the great Negro players who are not here only because they weren’t given a chance.”

Williams was referring to two of the most famous names in the Negro Leagues, who were not given the opportunity to play in the Major Leagues before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947. Gibson died in 1947, relatively early in life while still an active ballplayer, and thus never played in the majors; Paige’s brief major league stint came long past his prime as a player. This powerful and unprecedented statement from the Hall of Fame podium was

“…a first crack in the door that ultimately would open and include Paige and Gibson and other Negro League stars in the shrine.” **

Paige was the first inducted in 1971; Gibson and other contemporary Negro League stars followed Satchel throughout the next four decades.

On November 18, 1991, President George H. W. Bush presented Williams with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in the US.

One of William’s final public appearances was at the 1999 All-Star Game in Boston. He was transported to the pitcher’s mound in a golf cart, as by that point in life he was barely able to walk. He then took off his hat, and waved it to the crowd – a gesture that he had never done in his entire career as a player on the Red Sox. He was given a standing ovation, lasting several minutes.

By Paul J. Nebenfuhr

Copyright © 2014

*adapted from Red Smith, the dean of all sports-writers

** Ted Williams: The Biography of an American Hero, by Leigh Montville